The Post-Holdsworth Jazz Vocabulary for Modern Jazz Guitar

Feb 04, 2021Question by David Lesak Answered

Question:

Pretty much any search online for the latest up and coming Jazz Fusion artists seems to show an entirely different melodic/harmonic approach to that of the previous genres. I am talking about artists of the calibre of Scott Henderson and Frank Gambale, John Scofield and John Abercrombie and to some extent Pat Metheny (not because I do not rate him as an all time great, but because his vocabulary does not seem to be derived from the same sources - I don't think of him as a Fusion player) and Allen Hinds since the early '80s, and even Larry Carlton and Jeff Beck (Blow by Blow) and more recently Jack Zucker, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Tim Miller, Mike Moreno, as well as many others I have probably missed.

I have not included John McLaughlin either in the primary list of influences in this genre, because again, I do not feel that his vocabulary nor his technique played a particularly important part in the development of the genre in question, and the same goes for Al Di Meola.

I tend to feel that Allan Holdsworth was already using both a different technique - legato - and musical vocabulary than his musical peers way back in the '70s in his playing with Soft Machine. There were other players who were able to imitate his style, such as Bill Conners and John Etheridge and later the guitarist who continued Holdsworth's stint with Level '42, Steve Topping, but Allan was the true pioneer of this new genre. I remember John McLaughlin in an interview saying that if he understood what Holdsworth was playing he would steal his style.

I thought that much of Allan's approach and style of playing arose from the fact that he did not want to play the guitar as a typical guitar - he was looking to obtain the fluidity and angularity of the saxophone, and I believed that much of this was inspired by the work of John Coltrane. Yet I still don't hear the same musical vocabulary in Coltrane's lines that I hear in Allan Holdsworth, Tim Miller's playing or even Kurt Rosenwinkel's more outside playing.

I am not sure how well I am capable of expressing this question. I suppose what I am getting at is that when trying to understand certain genres of Jazz, and particularly Jazz guitar, it is possible to trace its development back to certain key influences, and certain names maintain their historic importance and are universally acknowledged, such as Wes Montgomery and Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt (who Holdsworth also claims as a major influence). But since the work of the artists I previously mentioned, there seems to have been an explosion of both styles and forms of expression that do not seem to me to be rooted in those approaches to improvisation and composition - neither melodically nor harmonically. And indeed there has also been a spill over into other genres, so that nowadays many rock players have also been influenced to some extent by this new wave of musical expression.

Jack Zucker also sought to express this saxophone like fluidity in his playing and in his teaching manuals, and indeed this is also why techniques such as sweep picking have become so important to these genres, as well as the legato technique.

There are many artists who have transcribed the work of Allan Holdsworth and pretty much all these players, yet the melodic/harmonic complexity that underlines these improvisations remains a mystery to me. I am aware that despite Allan Holdsworth's 'outside' playing, his lines weave in and out of the harmonic structure seamlessly, respecting the chord structure.

At the outset of his career, other Jazz players rejected him and accused Allan of not playing Jazz. This was why he was forced to take the decision to sell up and move to the USA. He was simply not able to enter the mainstream in the UK, and in fact was not recognized as the genius he is until relatively recently.

I don't understand how these players arrive at their melodic approach. What I am looking for is a means to capture the essence and flavour of these lines, rather than try to sound like any given player. It is difficult to know where to start, despite having already spent many years with this goal in mind. I suppose I have my own style already, but I feel limited in my expression.

Thank you for your patience reading this question and please forgive the lengthy nature of my post.

-David

Marc's Answer:

Hello David, thank you for you nice (long) question. I believe that you're right: you'd better get to the essence of the players that you'd want to sound like, rather than plainly imitating them Because I'm not a specialist (I have only 1-2 Holdsworth album on my shelf), and because I know someone who is knowledgeable, I'll let my colleague Matt Warnock answer. He wrote about three nice (and simple) ways to "bring out the modern" in you guitar playing in the form of exercises. I hope you like it.

Matt, Take it OUT!

3 Ways to Modernize Your Jazz Guitar Solos

When learning to play jazz guitar, many of us start off with the blues, modal jazz tunes and standards, often progressing into the bebop and hard bop realms as we develop our skills on the guitar and in the genre.

But, when we are looking to bring a more "modern" sound to our playing, many of us are unsure of where to start in the practice room in order to achieve this goal.

In this article I've laid out three different modern jazz approaches, namely:

4-note-per-string scales,

triad pairs and,

tritone division soloing,

... which you can bring to your to your jazz guitar improvisation that will immediately add that modern jazz sound to your ideas, and that are relatively easy to apply to the guitar and to tunes that you are working on.

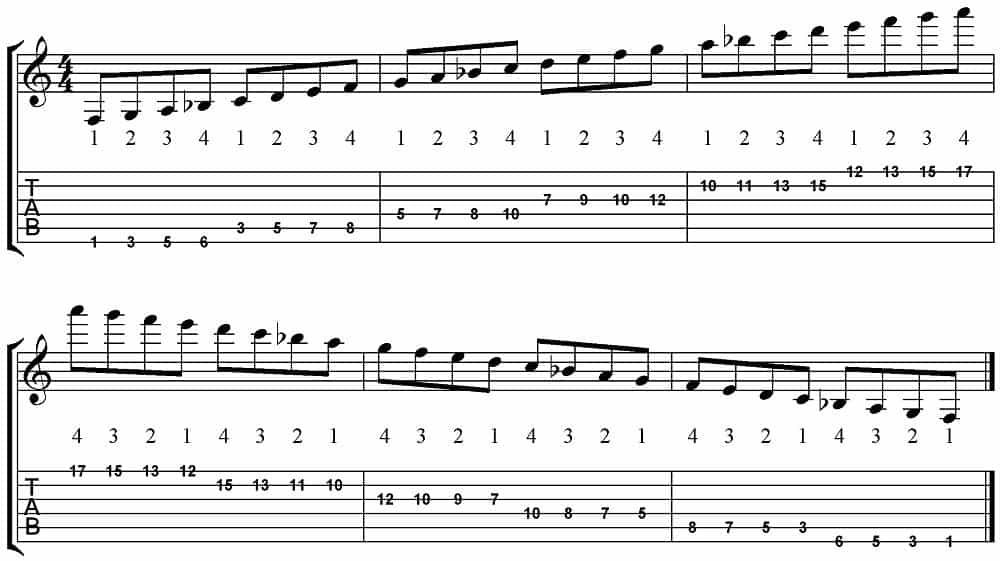

4 Note Per String Scales

The first modern jazz guitar idea we'll look at is playing scales with four-notes-per-string. I first learned this scale-fingering method from checking out Allan Holdsworth's playing, and later on from listening to Kurt Rosenwinkel talk about it during clinics and workshops.

The idea is pretty straight forward. You play any scale that you are focusing on in the practice room, but instead of playing it in position up the strings, you play four notes on each string, which propels you up and across the neck ascending the scale, then down and back the neck descending the scale.

When doing this, you'll probably have to think of each note in the scale, as you can't fall back on box patterns and traditional scale patterns to get your through this exercise. This is an added bonus when practicing these scales, that you are learning the notes on the neck and in the scales you are working on at the same time as you are playing them across a large area of the guitar.

Here is an example of an F major scale written out with four-notes-per-string, with the fingering added underneath each note as a reference.

Once you've checked out this scale in the key of F, take it to other keys across the neck, as well as to other scales such as the modes of the major scale, modes of melodic minor, modes of harmonic minor and harmonic major.

As well, you can add slurs to one or more notes on each string in order to get that "slippery" Holdsworth sound in your lines. Try playing a hammer-on between the first and second note on each string going up the scale, and then a pull-off on the first and second note of each string going down the scale.

The possibilities are endless when it comes to slur combinations on different strings, so feel free to explore this technique as far as you want in the practice room, with one, two or three slurs per string.

When you have this scale under your fingers, try putting on a backing track, just a one-chord vamp to start, say Fmaj7, and then improvise over that chord using only this scale fingering. This is where the rubber meets the road and you'll be able to take the technical side of the four-note-per-string scales and apply them to the musical side of improvising.

Though this approach will seem tricky at first, once you get it down it can really open up the neck for you, as well as give you a plethora of options when it comes to adding slides, hammer-ons and pull-offs to your lines and phrases, in the style of players such as Allan Holdsworth and Kurt Rosenwinkel.

Triad Pairs

The second modern jazz guitar technique we will explore is using triad pairs to improvise over chord changes. This approach has been used by many of the great jazz improvisers over the years, including Michael Brecker, David Liebman and Jonathan Kreisberg, and it is a fun and easy way to quickly add a modern flavor to your lines.

When improvising using triad pairs, you will pick a chord to focus on, for our examples we will use G7, and then you work between the triad starting from the root of the chord, and the triad starting on the 2nd note of the scale, the 9th, with both triads being of the same harmonic quality.

For G7, start by working between G and A triads, G-B-D+A-C#-E, two major triads paired up a tone apart. These are the two triads from the Lydian Dominant scale, which creates a G7#11 sound, another modern jazz flavor when improvising over dominant 7th chords.

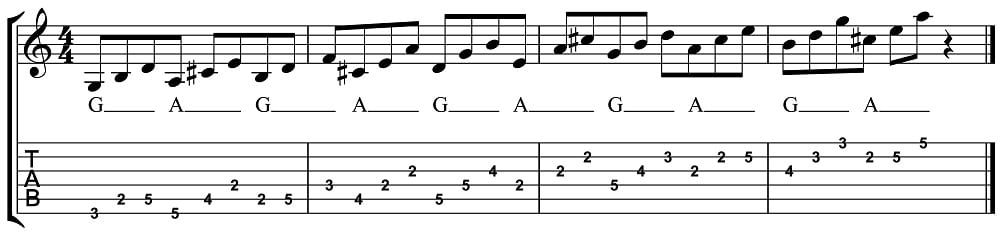

Here is how those triads would look on the neck in the third position of the guitar, moving between root position and the 1st and 2nd inversions of each triad up the neck.

Try putting on a G7 vamp backing track, then improvise over this chord while moving between the G and A triads. Here are some options to help you add variety to these three-note chords as you work them into your solos.

- Play both triads ascending

- Play both triads descending

- Play the first triad ascending and the second descending

- Play the first triad descending and the second ascending

- Repeat the above four techniques for the first inversion of each triad

- Repeat the above four techniques for the second inversion of each triad

So you can see that there is a lot of variety when using just these two, 3-note triads in your playing. As well, if you want to spice things up harmonically, you can add a passing triad in between the triad pair to create an inside-outside sound. For the case of G-A, you could add in an Ab triad to add an extra level of tension to your lines, G-Ab-A.

You can apply triad pairs to any chord you are soloing over, and as you get more familiar with them you can pair up triads that are more than a tone apart, but this is a good place to start. Here is a reference table to help you when you explore other chord types using triad pairs in your solos, written over the root note C.

- Cmaj7 = C+Dm (Ionian Sound)

- Cmaj7 = C+D (Lydian Sound)

- C7 = C+Dm (Mixolydian Sound)

- C7 = C+D (Lydian Dominant Sound)

- C7 = C+Db (7b9b13 Sound)

- Cm7 = Cm+Dm (Dorian Sound)

- Cm7 = Cm+Ddim (Aeolian Sound)

- Cm7b5 = Cdim+Db (Locrian Sound)

- Cm7b5 = Cdim+Ddim (Locrian Nat 9 Sound)

You can explore this approach much further with other interesting combinations.

Tritone Division Soloing

The third and final modern jazz guitar technique we will explore is the concept of Tritone-Division soloing. This technique comes from the great jazz trumpeter Woody Shaw, and is used my many modern jazz players to this day.

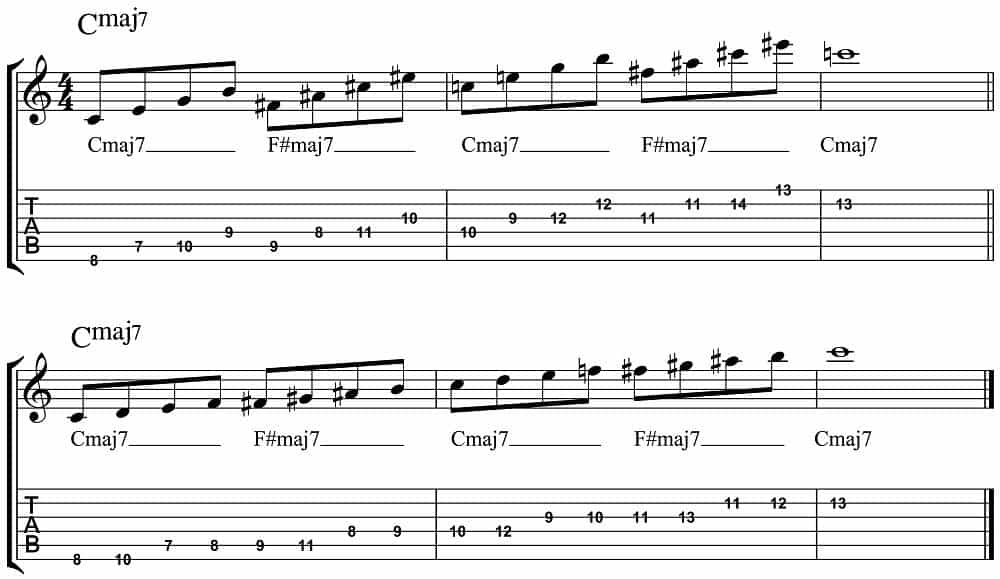

The concept is built upon the idea of taking the octave and dividing it into two equal parts, which produces the interval of a tritone. For example, over Cmaj7, as in the notation below, you start with the tonic, Cmaj7, and you divide the octave from C-C in half, which gives you the note F#. Then, you harmonize that second note with the same chord quality as the tonic, F#maj7, and you alternate between these two chords in your lines.

This means that if you were soloing over a Cmaj7 chord and you applied this concept, you would build your lines by alternating between a Cmaj7 and F#maj7 chord as you moved across the neck. This can be done in two ways, using arpeggios or using scales, and then of course mixing both of those ideas together.

If you are new to this approach, and to the concept of inside-outside playing, it's a good idea to start with the arpeggio approach first. This approach allows you to outline each of the two chords, producing the inside-outside sound, while you work with only four notes on each chord, making it easier to switch between the two on the neck until you are more comfortable with this harmonic pairing.

Once you have the arpeggio approach down, you can try moving between the two scales that come from each chord, in this case C major and F# major. In the example below I wrote out an idea that I like to work on where you play the first four notes of each scale, moving between the two chords as you move up the neck.

This is a good starting place with the scale approach as it allows you to move between both chords using their appropriate scale, while making a smooth transition between each chord at the same time.

Here is an example of how to apply the arpeggio and scale approach to a Cmaj7 chord, alternating between Cmaj7 and F#maj7 across the neck.

Once you've checked out these two approaches from a technical standpoint, try putting on a Cmaj7 vamp and improvising over that chord using first the arpeggio tritone-division and then the scale triton-division approaches. When those two ideas are comfortable as separate entities, then bring them both together, mixing scales and arpeggios over both chords as you build your lines and phrases.

You can apply the tritone-division technique to any chord quality you are soloing over, m7, 7, m7b5, m6, mMaj7, the key is to use two chords a tritone apart that are of the same harmonic quality. This means that if you wanted to apply this approach to G7, you would blow between G7 and Db7, both 7th chords a tritone apart.

Once you have this idea under your fingers and in your ears over a static chord vamp, try working it over a ii-V-I progression, a blues or your favorite standard. It is a fun way to instantly add a modern jazz sound to your jazz guitar solos, and one that is not that difficult to get under your fingers and bring into the jam room or out on the bandstand.