Jazz Guitar Arpeggios — Introduction

Feb 09, 2021What is an Arpeggio?

Arpeggios in music can also be described as "broken chords", or any instance of the notes of a chord being played separately. However, in jazz, learning arpeggios is slightly different than in classical music.

Jazz guitar arpeggios are the notes of a chord, played individually without any open strings. By eliminating open strings, the arpeggios become moveable "shapes" that can be used for all 12 keys. This is very useful for outlining chord changes during improvisation.

Jazz guitarists of all eras used arpeggios in their solos as a means to effectively “make the changes”. In this article, we will look into arpeggios derived from scale positions.

This "scale positions" approach is very effective, compared to the usual learning and memorization of arpeggios in “shapes” on the fretboard. Ready? Read on!

Up to the 13th (aka “complete arp”)

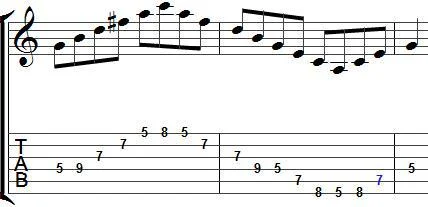

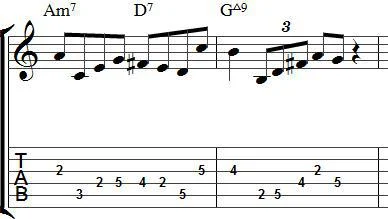

Let’s start with the widest possibility for arpeggios which has seven different notes in the arp. Let's start in G with the “6-2” position (see above linked articles) and play something like this:

The arp contains the notes G B D F# A C E G, which,

in “scale degrees” means 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 and 1.

In fact, this arpeggio contains all the notes present in the scale. That’s why it’s often called “complete”. It is the entire scale played in non-consecutive scale tones.

To clarify; this is the scale on two octaves, and the 13th “complete” arp is bold:

G A B C D E F# G A B C D E F# G

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1

I like to describe this type of arp as “playing the scale and skipping every other note” or, “playing the scale by third intervals”. When you see arps like this, (as non-consecutive scale tones) learning the proper scale positions will automatically unlock all the possibilities for arps in every position.

It is even more interesting and possible to unlock every arp for all seven major and melodic minor scale positions. It takes a bit of work, of course, but it’s well worth the effort! Go ahead and give it a try.

Play seven note arps in seven positions seven days a week! (Just had to say it.)

Points to keep in mind:

- No matter what position, you will be playing all the notes present in the scale (by third intervals).

- Make sure that you keep the original fingerings found in positions. Be strict at first, then come up with your own fingering concepts for playing the 13th arps.

- It will be tempting NOT TO stretch the index or pinky. Be careful and make your hand “stay” as much as possible. (See, The Definitive Guide to Scales Positions for Guitar)

- For every position, start on the root and go up as far as possible … then down as far as possible. (aka “completing the position”)

Some positions have more notes below, then above the root. Go as low as possible, no matter what. Here’s a good example (4-1 in G):

Give this a try, don't think too much, just play (!) the 13th arps in the seven positions in major, then in melodic minor. Try it for a while and you’ll notice stuff happening in your playing.

Don’t Forget the “Negative”!

And, just to double the amount of stuff you can work on, (thus doubling the possibilities when you improvise) notice that every seven note arp has a “negative”, like photographic film. It is the arpeggios “on the flip side” so to speak!

Here’s what I mean (in G major, “6-2” position) :

Each position contains a “starting on the root” seven-note arp, plus “the other way around”. You are playing every possible third interval in each position… all over the neck in major and melodic minor. This is great to know!

Again, go ahead, try it! If you do it in all 12 keys you will basically be playing ALL the available thirds (major and minor) on the entire fretboard. That is cool!

But, only thirds? (-;

Let's talk about the other arps in position (that are made of less than seven notes.) ...Triads and Seventh Chords

Arps are a powerful tool when used with scale positions. Check out this article to build that scale positions foundation: The Definitive Guide to Scales Positions for Guitar

Let's go on to the "small stuff"...

Diatonic Triads

It is time to look at the “smallest” possible arpeggios, triads. They consist of three notes, being the root, third and fifth. There’s a triad built on each degree of any scale.

The triads are only small segments of the 13th arps we played above.

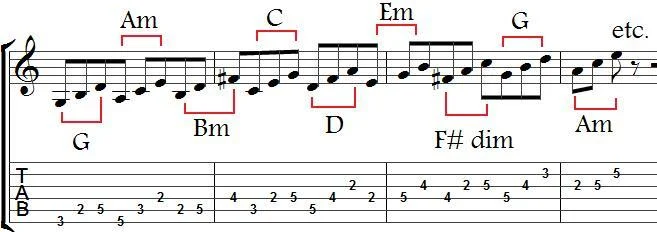

In the key of G major we get :

G, Am, Bm, C, D, Em and F# dim.

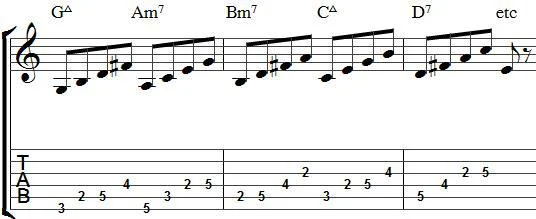

This is demonstrated in the “6-2” position here:

I encourage you to play the above in G melodic minor so you can hear and feel the difference. Try it on your own. The triads of G melodic minor are : Gm, Am, Bb augmented, C, D, E dim and F# dim.

Triads are often overlooked by beginning improvisers but they’re still very important. Every good jazz solo contains triads to a certain extent. Listen to bebop recordings and you’ll hear plenty of “disguised” triads (check out Charlie Parker heads like “Anthropology” and “Ornithology”!)

And, of course, triads are to be applied in the 7 positions of major and melodic minor. By doing so, you will really start to “feel” the positions and the sounds that can be made with them…

Make sure you keep the correct fingerings for each position!

Different Patterns

Other patterns are possible for triads. They’re shown above as 1-3-5 in eighth notes… but this could (and should) be practiced in all kinds of ways such as :

- backwards (5-3-1)

- with different rhythms (use quarter-notes, triplets, etc.)

- skipping and coming back (3-1-5)

- repeating a note (making them 4 notes such as 1-3-5-1)

- as inversions (see below)...

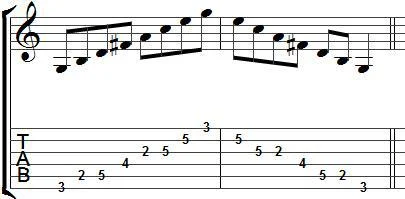

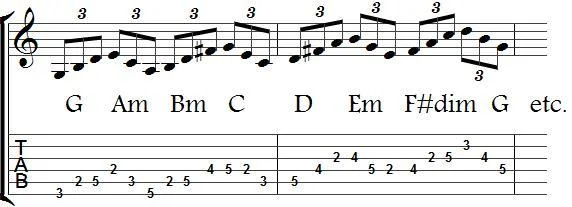

Here’s an example of a common pattern in triplets (in G major “6-2” again). The first triad is played upward (1-3-5), the second downward (5-3-1) and so on:

Don’t worry about finding ALL the patterns and playing them perfectly. It won’t happen! There’s just too much stuff out there for us to grasp in our lifetime… you have to choose small amounts of material and work at it.

Take a pattern you like and practice the heck out of it (in each position.) You may work a long time (weeks or even months) on the same pattern. Some positions are more difficult to master, but they will help improve your technique tremendously.

Diatonic Seventh Chords

We can apply the same concept we used for triads to get 4-note arps in a certain key. This gives us the diatonic seventh chords.

The key of G major:

G maj 7, Am7, Bm7, C maj 7, D7, Em7, F# min7 (b5)

Demonstrated in “6-2”:

Play this in G melodic minor. The seventh chords of G melodic minor are: Gm maj7, Am7, Bb maj7 (#5), C7, D7, Em7(b5) and F# m7(b5).

Seventh chord arpeggios are also to be played in the 7 positions of major and melodic minor. Keep the correct fingerings for each position.

The above demonstration uses 8th notes in an ascending way but, other patterns exist. The possibilities for different patterns becomes scary when playing four notes! Find and stick to something you like so you can work on it for a while.

A little “pep talk”:

You will unlock great fingerings and ideas for improvisation by figuring out the arps by yourself in each position. Otherwise, you would have to memorize “shapes” that could turn out to be completely useless for you.

You will make sense out of the guitar fretboard and understand what works best for you by learning position by position! Roll up your sleeves and get to work because the process is the reward!

Running Changes

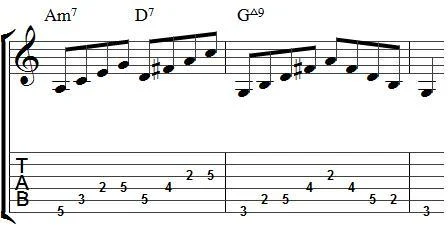

You can start applying diatonic triads and seventh-chord arps to chord progressions once you get familiar with them in most of the positions. One of my favorite ways is to isolate the II, the V and then the I.

Here is an example in G major, “6-2” position:

I find the example above just plain and boring but that is the main concept. Find different ways of playing the chords and arps. Create lines like these II V jazz guitar arpeggios.

More to do: Extensions and Inversions

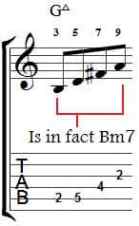

Build up to “higher” chord tones using the concept we've discussed for triads and seventh chords. Play a 1-3-5-7-9, or even a 3-5-7-9.

Consider this for a moment; a 3-5-7-9 for G major 7 is B-D-F#-A. These are the same notes you get from a Bm7 (seventh) arpeggio. When playing on a G major 7, play the extensions 3-5-7-9, thus playing Bm7 over G major 7. Charlie Parker was known to do this. He would blow on the extensions of chord progressions.

Example:

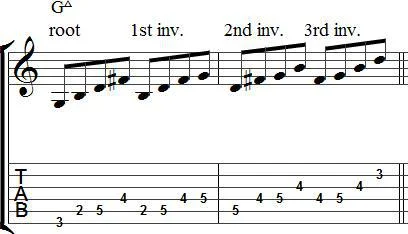

Arpeggio inversions are also very common practice in jazz improvisation. I won’t go into details, but it implies starting the arps on notes other than the root, and playing it up or down.

Create different intervals by keeping the exact same notes in the arp. This adds new sounds to the very same arpeggio.

Example:

This is something to consider.

Arpeggios Wrap-up

We looked at:

- Triads in positions

- Seventh chords arpeggios in positions

- Running II-V-I changes using arpeggios in positions

- Arps extensions and inversions