Chord Substitutions

Apr 20, 2021The Jazz Guitarist's Survival Guide

We can reharmonize any chord progression in just about any style of music. Chord substitutions can be described as what I like to call "new harmonies with the same function." However, this isn't necessarily a black and white thing as you'll see throughout this lesson.

This lesson will address the substitution of harmony on a "chord-to-chord" basis and then moves onto more abstract concepts.

Here are the substitutions we will go through in this lesson:

Part 1 Chord by Chord Substitutions

- Diatonic Chord Substitutions:

- Dominant Chords Alternative: Diminished

Part 2 On Chord Progressions

- Interpolation and Back Cycling

- The Tritone Substitution

- Changing the "Color"

- Bass Note Reharmonization

Being able to take liberties with the harmony of a given tune is an important skill set for jazz guitarists to have in their arsenal.

The practice of employing these reharmonization techniques help to deepen the harmonic vocabulary and understanding of how chord progressions really work for any jazz musicians. At times, you will find that many choose to blur the lines in regard to harmonic function.

Part 1 — Chord by Chord Substitutions

When you examining one specific chord inside a progression it is possible to find alternatives. The most common way to look at this is to find chords that share common notes.

First, Diatonic Chord Substitutions:

It is easy to find chords with common notes with the help of a key signature. Go ahead and examine the 7 chords in a given key. You will find that every chord has an alternative. The way to find these is simple: each diatonic sub is separated by a diatonic third.

Let's explore this.

In the key of C: Cmaj7 can be substituted for Am7 or Em7.

Cmaj7 (C E G B) shares three notes with Am7 (A C E G)

(A is a third below C)

&

Cmaj7 (C E G B) shares three notes with Em7 (E G B D)

(E is a third above C)

Let's conduct a little experiment.

In the context of a band, if you play Am7 while the bassist is playing C root, it sounds like C major 6th. Pretty neat, right? Again, in a band context, if you play Em7 while the bassist is playing C root, it sounds like C major 9th. How is this happening, exactly? The following diagram shows us that an Em triad is the same as Cmaj7 without the root.

When you add the b7 to that Em, you get a D which is the 9th of C.

Other chords in the key - or outside of the key, for that matter - may offer interesting options for jazz guitar chord substitutions. They are yours to discover. Analyze, research, explore to make sure it sounds good to you! It is not as simple as merely knowing the musical math. You have to figure out which voicings fit the best and which you might want to avoid in certain situations.

Second, Dominant Chords Alternative: Diminished

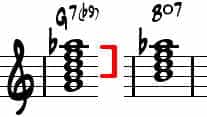

While still exploring common tone substitutions, let's get into a specific chord type: [vintage horror film tone] the dreaded dominant 7b9 chord! The spelling for this chord is fairly simple; 1 3 5 b7 and b9. It can be used as a resolution in most V-I situations such as G7b9 to C.

The beauty of the dom7b9, as we'll see in a second, is in its symmetrical nature when we omit the root. We're left with a Bdim7 when we leave out the root in a G7b9 chord.

The dominant will get the symmetrical characteristics of its related diminished in heritage! That's like the chord's "genetic code".

A little theory refresher:

Since the diminished chord is symmetrical in nature, it is movable up and down in minor 3rds. In other words, Bdim7 is, in fact, the same chord as B, D, F, and Ab diminished. They all contain the same notes.

Note Don't forget their enharmonic equivalents! Ab = G#, and so on.

Try it for yourself. Do you hear how each of these is a possibility over G7b9?

Or, more simply, play a diminished 7th chord from the 3rd, 5th, b7th or b9th of any dom7(b9) chord.

Part 2 — On Chord Progressions

By examining a specific progression it is possible to find alternatives. The most common way to look at this is to find progressions that share the same destination.

First, Interpolation and Back Cycling:

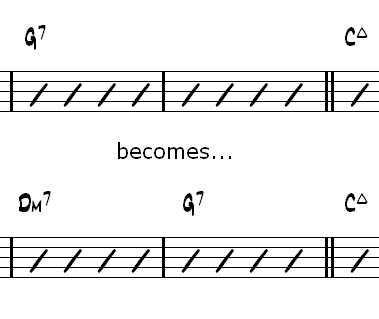

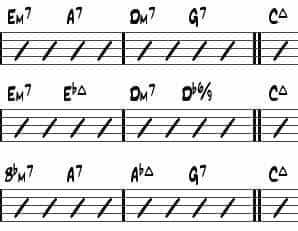

Jazz musicians play the II-V cadence most of the time when resolving to the I chord. Therefore, the V-I can become II-V-I. This concept is known as interpolation.

In this example, let's try adding the V's related IIm7 chord before it.

This principle works fine even if there's no resolution to the I chord. Simply add the appropriate II chord in front of the V. A good place to try this is in the bridge for any "rhythm changes" tune. Each dominant chord is a target for its previous chord! In other words, they're all kind of acting as a I chord temporarily.

Make sense? Alright, so let's go back to resolving to the I chord.

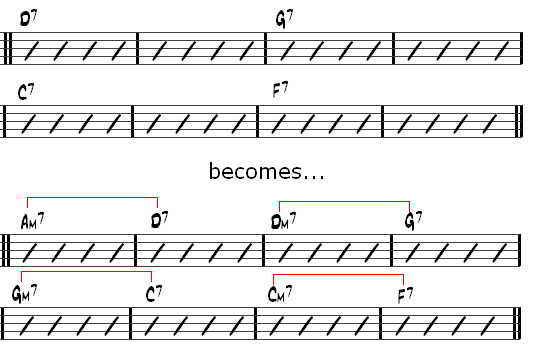

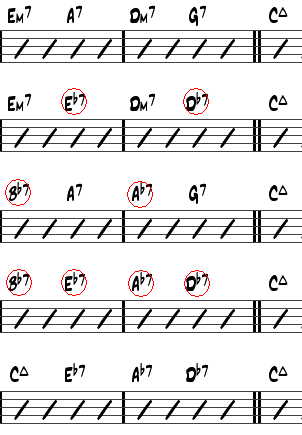

Previously, we had V-I becoming II-V-I. Next, we can add another II-V a whole-step above this II-V to get III-VI-II-V. Further, we could even add one more II-V upfront. This would mean our progression now begins at the #IV, which is F# if we're in the key of C.

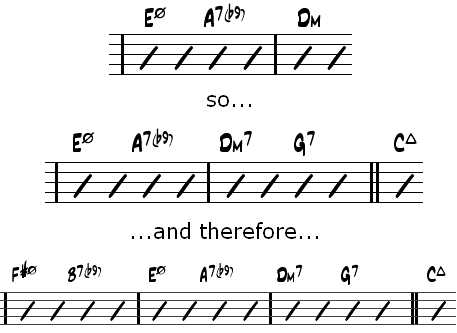

This concept is called back cycling. The added II-Vs each contain the dominant of the next II chord. In other words, A7 is the V of D, G7 is the V of C, and so on. Beyond the II-V to the tonic chord, these back cycling progressions should be treated as minor II-V progressions. In other words, m7b5 to dom7b9.

(see below)

Naturally, other possibilities exist. Once again, the other chord substitutions are yours to discover. Listen to pianists and guitarists on jazz recordings and find your own favorite back cycling tricks.

Second, the Infamous Tritone Substitution (at last!)

This type of substitution is the classical Neapolitan Sixth for dummies. Uh, I mean, for jazz musicians! Sorry (-;

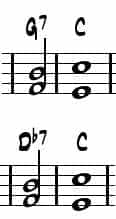

Two dominant chords that are a tritone apart (three whole-steps) share the same 3rd and b7th, except they are inverted. (see below)

The interval created by the 3rd and the b7th is commonly known as a tritone. That can be a little confusing!

The tritone is a raised fourth or a diminished fifth.

Remember, dominant chords that are a tritone apart share the same tritone! The presence of this tritone interval means that the bII chord has the same function as the V chord. Why? The tritone interval, present in both V and bII, tends to resolve the same way to the I chord. Try it!

That's it for the theory side of tritone chord substitutions. Phew!

Still there? Good!

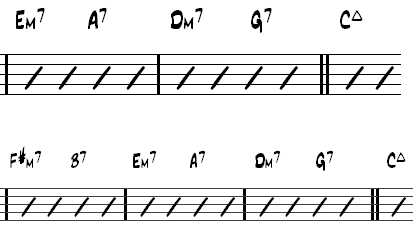

All tritone substitutions do is make your dominant-to-tonic resolutions go down in semitones as opposed to going up a fourth. Jazz musicians use this concept freely in composition, improvisation and comping. In the following example, the basic III-VI-II-V-I is used to demonstrate the alternate chords. (see below)

Third, Changing the "Color":

This one might seem a bit obvious but I want to talk about it briefly. It's like the "cherry on top" for jazz chord substitutions.

Any chord can be played using another color. It works particularly well on chords than have already been substituted. For instance, if you use a tritone sub of Db7 instead of G7, you can make that chord a major 7th, diminished, major 6th, or whatever you want.

The main consideration with this is to be aware of the melody note when applying it. In other words, watch for any clashes or strangely voice intervals.

This is a great compositional and improvisational device. It creates great contrast and can give the substitution less of a "clunky" feeling.

Here are some examples using the same progression as above:

Bass Note Reharmonization

Another really nifty technique is to simply use the bass note as the focal point for your reharmonizations. It's actually really neat how moving around one note can yield a bunch of different sounds. This is usually up to the bass player, but if you're playing in a solo or duo setting, you can take advantage of some of this stuff as well.

Let's see how we can make this work for us.

If you have an Em7 chord, adding a C in the bass would create a Cmaj9.

C E G B D

Let's try the same idea against a C major triad by adding A to the bass. This one gives us Am7.

A C E G

So far, these have all been pretty standard and mostly based on diatonic substitutions. Let's try something a bit more adventurous.

If you have a G major chord and you put an A in the bass - a whole step up from the root - it gives you a cool sus type of sound. A G(7) B(9) D(4)

A G B D

I definitely suggest exploring this idea and seeing what kind of cool sounds you can come up with. Always analyze your findings and take them through different keys to make sure you've got it!

Final Words

There is a lot more to understand in chord substitutions. I could write a book (or two) about it, but it would be pointless to simply read about it. Real music comes from experimentation and practice. It's best to learn from recordings, in rehearsals and attending concerts.

I established the basics on this page. Now it's your turn to go on and find out what kind of substitutions you like. Keep your ears wide open and you'll always discover new fresh ideas.

Have fun!