The Ultimate No Nonsense Guide to Jazz Harmony

Oct 31, 2017UPDATED information on II-V-I, jazz chords, progressions, lead sheets, cadences, secondary dominants and more ...

Jazz harmony is defined as the theory behind jazz chords, and the ultimate practice of how jazz chords are put to use in the context of jazz music. Since American jazz music resembles, in analysis, other practices of Western harmony (i.e. classical music), jazz harmony and theory relies heavily on similar concepts such as scales for the foundation of chord construction.

This page hosts straight-to-the-point answers to common questions about jazz chords, jazz chord progressions and harmony in general. No frills. Just plain and simple explanations of how chords work together and why. Ever wondered about “two five’s” (ii-V), cycling, cadences and interpolation? Then read on!

While learning about jazz harmony here, some questions may arise. It’s ok! They are most likely answered somewhere on this very same page. If not, please contact me.

Table of Contents

Jazz Chords Part I

- What is a II-V-I ?

- What is a II-V ?

- What’s the difference between “major two five” and “minor two five” ?

- How does the II-V-I actually work ?

- What is a cadence ?

- What is an “unresolved cadence” ?

- Why use roman numerals ?

Part II

- What is a secondary dominant ?

- What is “ii-V interpolation” ?

- What is Back Cycling ?

- What is I-VI-II-V ?

- What is a turnaround ?

Part III

- What is a tag ?

- What is a back door progression ?

- What are “chord tones” and “guide tones” ?

- What are chord extensions ?

- What is an altered dominant ?

- What is an inversion ?

Part l

What is a II-V-I ?

The fundamental (and most used) cadence in tonal jazz music. This common jazz chord progression contains three diatonic chords. [Diatonic means: pertaining to a specific key.]

In all major keys, we can obtain 7 diatonic chords by harmonizing the scale in 4-note chords built in thirds. (see this page for diagrams and explanation on diatonic chords)

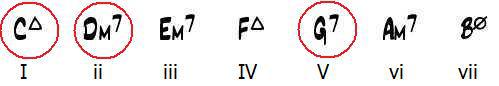

We’ll use C major to demonstrate. We have:

The triangle means “major 7th”, the dashed circle means “minor 7th (b5)” We need three jazz chords to create the ii-V-I: the second degree, the fifth and the root (circled in red). (See "Why Use Roman Numerals?" below)

Therefore, a ii-V-I in C major is spelled:

You’ll see this progression everywhere in jazz standards and modern compositions. It’s probably the most powerful “harmonic trait” in existence! It’s often very well hidden in more modern jazz tunes (different chord qualities, inversions, rhythmic displacement, and so on…)

If you’re not familiar with this yet, learn to identify ii-V-I cells by sight and sound! Watch out : it’s not always in the key of C though!

Here’s a little jazz chords ii-V-I reference chart in all the keys:

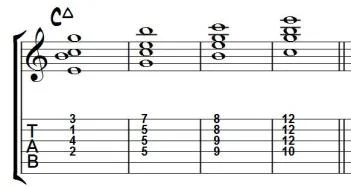

Jazz chords for guitarists this time: ii-V-I voicings chart for guitar (in all keys) using basic shell voicings (root, third, seventh only):

What is a II-V ?

Simply put: a ii-V-I without the I. Because we are missing the I here, we could call this an unresolved cadence. See what is an unresolved cadence. For instance: Dm7 – G7 (there’s simply no C chord after).

It’s almost as common as the full version ii-V-I and can be found mainly in jazz compositions from the bebop era and on. Learn to identify ii-V cells by sight and sound (also). All you have to do is remove the “one” chord from the above PDF’s and you’ll be set.

Important: Keep the “I” chord in mind as the point of reference at all times in a ii-V (yes, even if the “one” chord is not being played at all). It is the “chord of destination” that matters the most! For instance, if you see Gm7 to C7 on a chart, you need to make this logical (and conscious) connection in your mind:

“Ok, so this is Gm7 to C7. It is a ii-V in F major”

Not sure?

I’ll use Stella by Starlight to further demonstrate. Here’s how the first 16 bars of the tune go in “logical terms”:

- ii-V in D minor

- ii-V in Bb

- ii-V-I-IV7 in Eb

- I (Bb) for one bar

- ii-V-i in D minor

- ii-V in Ab

- F for one bar

- ii-V in F

- ii-V in G minor

- [that’s the bridge]

- etc.

Interlude

I love books. At this point I have to recommend two cool jazz books I have in my library. The first one is by David Berkman and it’s called the Jazz Musician’s Guide to Creative Practicing. It’s easy to get lost in the theory, and the author gets you back on track.

Coincidentally, David Berkman also wrote The Jazz Harmony Book recently. His efforts align with mine: make things clearer for anybody interested in the topic of jazz harmony and chords! He’s a piano player so his explanations are probably even neater than mine.

What’s the difference between major two five and minor two five ?

The major and minor qualify the chord of destination at the end of the cadence (the I or tonic). For a major ii-V-I, we use good old Dm7 – G7 – Cmaj7 (key of C major).

For a minor ii-V-i though, we have to alter the chord qualities to fit the minor sonority of the progression… The ii, V and i chords will then have one (or a few) different notes because they come from a minor scale. Here’s the spelling for a minor ii-V-i in C:

Dm7(b5) – G7(b9) – Cm

The ii chord has a flatted 5th (aka a “half-diminished” chord) and the V is an altered dominant. The easiest explanation for this minor ii-V-i is tracing back its origin in the harmonic minor scale. Caution: the harmonic minor is NOT the only explanation for the minor ii-V-i.

The Theory:

C harmonic minor scale : C D Eb F G Ab B C

(same as major except b3 and b6)

First, this scale contains the Eb that:

- Acts as the “flat 13” of G7 (altered dominant)

- More importantly, gives us a minor “one” chord, our friend C minor.

Secondly, C harmonic minor contains an Ab, which acts as:

- the “flat 5” of Dm7(b5)

- the “flat 9” of G7.

How does the II-V-I actually work ?

Tension is created, and then resolved. Within the progression are the mechanics of this fundamental harmonic cell. The notes contained in the present chord create a tension that is resolved into the next chord.

Here’s the simplest explanation:

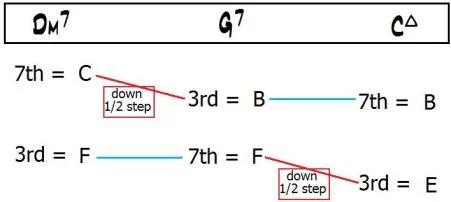

Resolution of the 7th descending by a half-step onto the 3rd of the next chord.

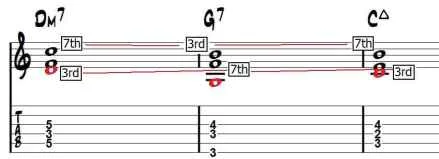

You may want to re-read this many times (out loud!) A picture is worth a thousand chords, so, here are shell voicings again (root, 3rd and 7th):

Disregard the root in red.

We observe two important motions in the half-steps:

- C to B when going from Dm7 to G7

- F to E when going from G7 to Cmaj7

This is called voiceleading.

This is what creates the tension and resolution. To put it in words: The seventh of the current chord has a tendency to resolve down to the third of the next chord. And the third of the current chord has no tendency and is sustained to become the seventh of the next chord.

Isn’t that neat?! Jazz chords just behave this way. Perhaps it’s clearer here:

Explain Cadence ?

Perhaps the most important question on this page! Very briefly, a cadence is a concluding type of tension and resolution in harmony (a chord progression). The end of a cadence is where music comes to a rest. (Music “lands” on the tonic, so to speak.) Notice that not all jazz chord progressions are cadences.

Evidently, the Wikipedia cadence article is much more complete than this humble article… but read on if you’re interested in the “shortcut” version!

A typical cadence contains all the following chords:

- Pre-dominant –> ii or IV (or even iii or vi)

- Dominant –> V7 (or sometimes a vii of some sort)

- The tonic –> I (or something else)

The chord that creates tension is called the dominant (the V found on the fifth degree.) It often has a 7th to heighten the degree of dissonance (and therefore raise the urge to resolve back to “I”) See “How the II-V-I Works.”

Some common examples of cadences:

In classical music:

- C – F – G – C; (I-IV-V-I)

- C – Am – G – C; (I-vi-V-I)

- C – F – C; (I – IV – I)

o This last one is called a plagal cadence, the “Amen” chords

In jazz music:

- Dm7 – G7 – Cmaj7 (iim7-V7-Imaj7)

- Cmaj7 – A7 – Dm7 – G7 (I-VI7-iim7-V7)

- Em7 – A7 – Dm7 – G7 (iii-VI7-iim7-V7)

o Called a turnaround

What is an Unresolved Cadence ?

Often, a cadence will not even resolve to its assorted I (tonic). The tension in the dominant is NOT resolved and the music just goes “somewhere else” so to speak.

Music (classical) theory buffs usually call this a deceptive cadence:

- C – Dm7 – G7 – Am (I-ii-V7-vi)

o (progression resolving to “vi” instead of the “I”)

In jazz, from the bebop era and on, musicians used unresolved cadences in form of “standalone II-V’s” (with no I). Jazz composer and improvisers started to use the II-V cell as a device/color, more than as a concluding progression or cadence.

You could hear it as a II-V for the sake of a II-V. It even possible to have a stream of II-Vs in different keys to create a certain effect (and to be used as vehicle for improvisation, of course.)

For example, the first 8 bars of the John Coltrane tune Lazy Bird:

|Am7 / D7 / | Cm7 / F7 / | Fm7 / / / | Bb7 / / / |

|Ebmaj ///| Am7 / D7 / | Gmaj7 /// | Bbm7/ Eb7/|

Let analyze this. We have four different II-V cells above :

- Am7-D7

- Cm7-F7

- Fm7-Bb7

- Bbm7-Eb7

It is fair to say to that #2 and #4 DO NOT resolve in a traditional sense. BUT …

- Cm7-F7 is going *clearly enough* towards Bb7 sooner than later!

- Bbm7-Eb7 is used as a “side slipping” device to go back to Am7-D7 when repeating the whole 8-bar section (identical II-V cells a 1/2 step apart, widely used in jazz)

We can also draw examples from some songs in the “standard” repertoire. The first 8 bars of the tune Out of Nowhere:

|Gmaj7 / / /| / / / / | Bbm7 / / / | Eb7 / / /|

|Gmaj7 / / / | / / / / |Bm7 / / / | E7 / / / ||

As an exercise, try to find examples of II-V cells that don’t resolve in jazz tunes that you are familiar with.

Why use Roman Numerals ?

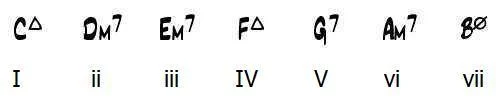

We assign numbers to chords built on degrees of a scale. For example, in C major scale we say that the C chord is I, the Dm7 chord is ii, the Em7 chord is iii and so on.

The capital-letter roman numeral implies a major triad (such as major 7th or dominant 7th structures) while the “small caps” ones imply a minor triad (such as a minor 7th, minor 7th(b5) and diminished chords):

Ok, but “why use them in the first place !?” might you ask. Here is the short answer:

Music is played in many different key centers. We always assign the roman numeral I to designate the tonic which is the “home base”. (aka the tonality or key in which the music is being played). Using numbers, we relativize the jazz chords and progressions to understand the logical/mathematical relationships between chords more easily.

The music can then be played from any key (from any “home base”) because the same principles / progressions applies to any/all of the keys. Everything becomes relative once you understand the use of numbers (instead of letters) in jazz chords and harmony.

Here’s something else for you to think about; the picture below depicts the seven diatonic chords of C major AND F major:

Please note:

The tonality (the key) can last for a whole piece or it can change. If a piece moves through different key centers, we use the term key of the moment for analysis.

Another note:

It’s common to use “all caps” roman numeral and add the chord qualities like this:

instead of

I-VI-ii-V

It doesn’t matter, all you have to do is make sure you understand “what’s what” in jazz chords! (-:

Part ll

What is a Secondary Dominant ?

A dominant 7th chord that is NOT built on the fifth degree (V) of the current scale. Or: Any dominant 7th chord that resolves somewhere else than on the tonic (I) by means of of a “V – I” cadence.

Here’s why:

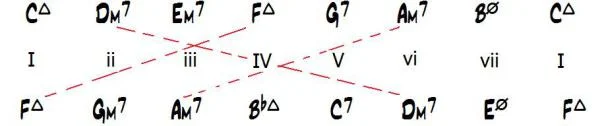

We know we can find the dominant chord on the fifth degree of the major scale. For instance, if we are in C major, the dominant (V) is G7. A secondary dominant is built from another note (NOT the V) and progresses (aka “wants to resolve”) towards other chord(s) in the key (and not the tonic.)

In the key of C, outside of the G7 acting as a dominant, we also have the chords A7, B7, C7, D7, E7, F#7 available as secondary dominants, functioning for the other diatonic chords.

To get there, we simply have to ask “What is the V of […] ?” for every chord in the key. For example, if we look at the Dm7 chord in the key of C, we will find that A7 is dominant by asking the question: “What is the V of ii ?”

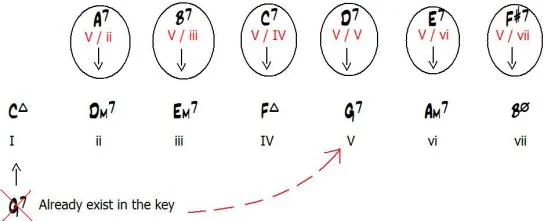

Therefore A7 is a secondary dominant, and it could create a cadence towards Dm. We call the A7 chord the “Five of Two”, or in symbol “V / ii”. If we do this with all of the diatonic chords in the key, we get :

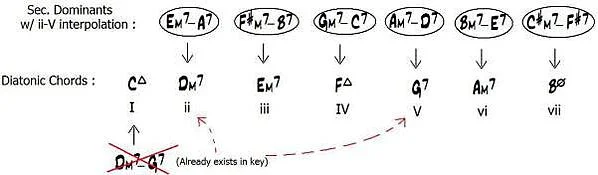

We therefore have six more jazz chords to be considered almost diatonic in any major key. These secondary dominants are closely related to the key because they have a function, a role to play. That function is resolving to the ii, the iii, the IV and so on. Now, a major tonality has 13 chords instead of just 7 ! Let’s keep exploring this idea in the next topic, ii-V interpolation.

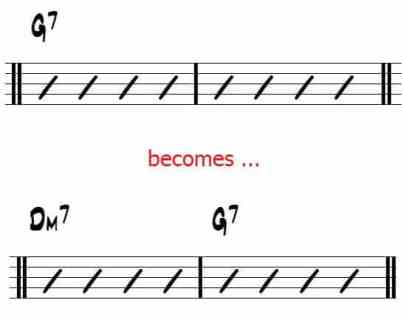

What is “ii-V interpolation” ?

Creating a IIm7-V7 cadence from a single dominant 7th chord. In other words:

Playing a “ii-V” instead of just the “V”.

In other words: when confronted with a single dominant 7th chord, adding a minor 7th chord a fifth above. It’s common to play more than one jazz chord when confronted with a single symbol on a chart…

Example of ii-V interpolation:

This has already been discussed on another jazz chords page on JazzGuitarLessons.net. See the interpolation topic in the chord substitutions article here. Interpolation is often used in traditional and/or contemporary jazz as a technique to develop improvisations, accompaniment or even composition and arranging.

We can use ii-V interpolation with any dominant chord… including the secondary dominants (see above). Here are the 6 secondary dominants with interpolation (in C major):

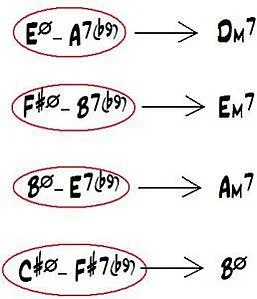

Of course, it would be wise to use minor II-V’s when resolving to minor jazz chords (the ii, iii, vi and vii in a major key). It that case, the interpolation would yield different results:

(This is just another set of possibilities, not a rule)

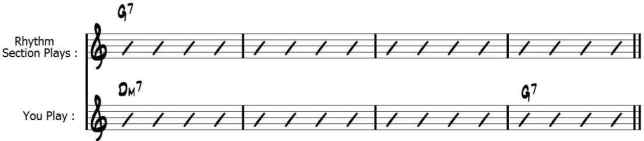

Addendum: Interpolation

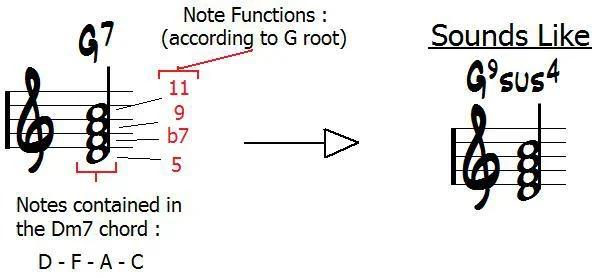

Interpolation can also happen “in the moment”, as a chord substitution device, where the improviser or the accompanist plays the related “ii” minor chord while the rhythm section “stays” on the “V” dominant chord. For example :

When you sound the notes of the Dm7 chord against a G7 (what the rest of the band plays), the result is a “dominant 9th w/sus4”: Here’s what happens.

This way of thinking can be applied to create interest through suspensions/resolutions in otherwise bland and plain chord progressions. Learn your II-V-I formula in all keys and try it on the spot. You’ll be amazed!

What is Back Cycling ?

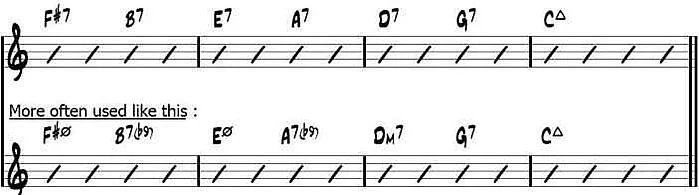

Use a string of consecutive dominants and/or ii-V cells in front of one another to cycle back to a destination chord (often the I). The result is jazz chords in a root motion through the circle of fifths. Like this:

This topic was also previously discussed on JazzGuitarLessons.net. Please refer to the chord substitutions article. Back cycling more often makes use of ii-V cells (and not just plain dominant 7th chords.) Notice that, on the second stave of the picture above, each dominant chord is the secondary dominant of the next minor 7th chord.

Another way to look at it: Back cycling is a series of secondary dominants with ii-V interpolation a whole step apart played back to back.

In C major, step by step:

- II-V (this is Dm7-G7)

we add another II-V cell a whole step up … - III-VI – II-V (this is Em7-A7 – Dm7-G7)

once again …

- IV-VII – III-VI – II-V (this is F#m7-B7 – Em7-A7 – Dm7-G7)

(Note : in back cycling through chords, it’s possible to use either major OR minor ii-V cells.)

This device is very interesting to spice up harmony and recorded jazz history has numerous examples of its' applications. It’s been used extensively in arranging, chord melody, improvisation and even composition.

Back cycling was used a lot by the late jazz guitar legend Joe Pass. If you really like that sound and want to learn more about jazz chords, I recommend you get the “Joe Pass Guitar Chords” (under 10$ on Amazon.) Joe himself explains his back cycling techniques in detail.

What is I-VI-II-V ?

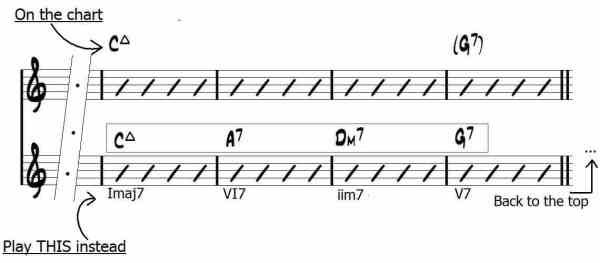

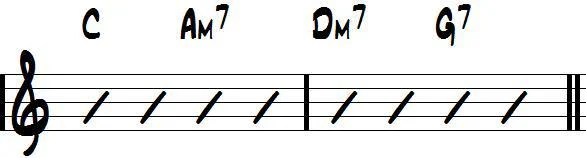

I-VI-II-V is probably the most common turnaround progression used in jazz harmony. (see “turnaround” below)

I consider the I-VI-ii-V to be simply an extended version of the most basic ii-V-I cadence. By incorporating the VI as a dominant, we create extra tension because it functions as the secondary dominant of the ii chord. The I-VI-ii-V is often used as a turnaround at the end of a piece. It is definitely better than just “sitting on the I chord” for two bars! For example :

You can also find the I-VI-II-V progression in the first few bars of “I Got Rhythm”. The standard song form with jazz chords being two bars each this time. (usually in Bb major) For variety, try changing the chord qualities in the I-VI-II-V progression. Learn more about the I-VI-II-V in this Jazz Chords (Progressions) article…

What is a turnaround ?

It is a cadence, applied at the end of a tune (or a section of a tune) to bring the harmony back to the top. Typical turnarounds usually:

- start with a tonic (or tonic-like) sound such as a I or iii, and

- end with a dominant (or dominant-like) sound such as V or bII

Examples of common jazz turnarounds:

(very diatonic)

(very common, VI is a dominant)

(all dominant 7th qualities)

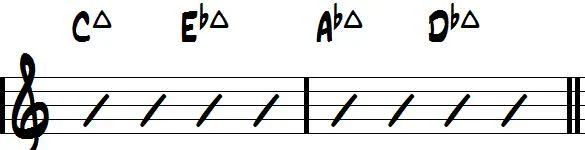

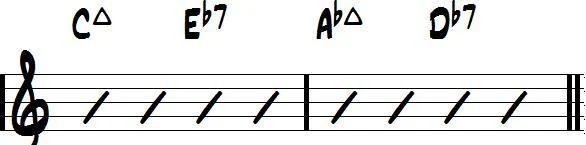

(all major chords, ala Tadd Dameron on “Lady Bird”)

(Tadd Dameron modified)

My personal favorite is the last one. I like the vibe of it very much. Note that the two “Dameron” turnarounds are basically tritone substitutes of the good old I-VI-II-V (see the above I-VI-II-V topic).

More turnarounds…

(jazz chord turnarounds using back cycling, secondary dominants, tritone subs, etc.)

Em7b5 – A7 – Dm7 – G7

(back cycling from iii)

E7 – A7 – D7 – G7

(back cycling w/all dom 7th)

Em7 – Eb7 – Dm7 – Db7

(w/tritone subs)

Ebm7 – Ab7 – Dm7 – G7

(this is called “side slipping”)

Cmaj – C# dim7 – Dm7 – G7

(with #I as an ascending passing diminished)

Em7 – Eb dim7 – Dm7 – G7

(with biii as a descending passing diminished)

Cm – A7 – Ab7 – G7

(with the bVI chord, often in a minor key)

etc.

There’s many more turnarounds to be discovered in jazz tradition. I’ll let you study your favorite jazz standards and find, analyze and apply other common turnarounds.

Part lll

What is a tag?

A tag is an added section of music that helps finalize the performance of standards or even jazz tunes. It is usually referred to as “tag ending” by jazz musicians. In the classical world, the term coda is usually employed to describe this concept in the musical form.

The harmonic and melodic material found in common tags is drawn from the last few bars of music in the tune and is repetitive in nature. A good rhythm section can usually wing a decent tag by repeating the jazz chords of the last 2, 4 or even 8 bars of the song. This is how jazz musicians create a “coda” from thin air!

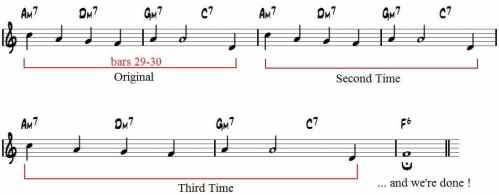

Here’s a common example of repeating the melody and the chords from the last few bars of music on a jazz standard. To end the tune “Days of Wine and Roses” in F, we proceed to repeat bars 29-30 three times before ending on the tonic chord; like this:

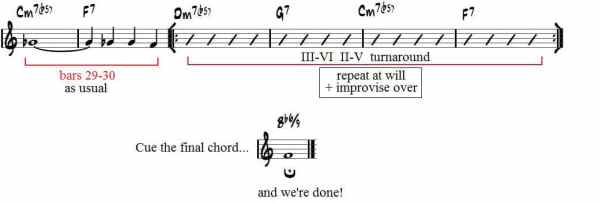

Sometimes, the tag can be used as a whole new section to improvise over before definitely ending a piece. The rhythm section loops the chord changes of the tag and the soloist keeps on improvising until everyone feels it’s time to end the piece, on cue. Here’s a common example of tagging a chord progression to improvise over as an ending. To end the tune Stella By Starlight, we …

- play bars 29-30 as usual

- avoid the “I” chord in bar 31 and play the “III” chord (Dm7) instead

- play turnaround progression starting on that “III” chord

- improvise for a little (or for very long!) on the repeated turnaround

- we cue the ending on the tonic chord Bb.

In short, avoid the I, go to III instead and loop the III-VI II-V to take a solo over… Thus creating two II-V cells a whole step apart! A Montreal jazz veteran (saxophonist Dave Turner) once told me that at some jam sessions, this type of “III-VI II-V tagging thing” with multiple horn solos could last longer that an entire tune!

There exist many more ways to end tunes with tags or different codas. Investigate! See what you like.

What is a back door progression ?

Similar to a ii-V-I cadence, the back door progression consists of the chords “IVm7 – bVII7 – I”.

In C major, it spells out: Fm7 – Bb7 – Cmaj7, like in the first few bars of the Tad Dameron tune Ladybird.

Some like to say it’s a “minor-third-up" type of chord substitution because Fm7 – Bb7 is a minor third higher than Dm7 – G7 (all in C major). Personally, I just like to call it a "back door progression". This device is often used in standards, progressions, jazz compositions, arranging, comping, and improvisation.

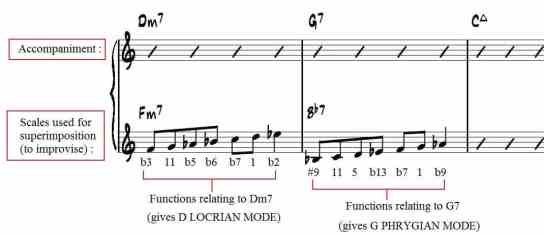

A common example of using the back door in improvisation is to purposely superimpose the scales and arpeggios from the back door while the accompanying jazz chords are a normal ii-V-I. On a ii-V-I in C, use the scales from Fm7 – Bb7 like this:

Superimposition of this kind is reminiscent of the minor ii-V sound… as the Fm7 – Bb7 comes from the key of Eb major. C minor is the relative minor of Eb major! So the superimposed scales of Fm7 – Bb7 create a C natural minor sound. Please note that you can do the same while comping! (can you?)

But why name it the “back door”? We call this progression a “back door” because it resolves to the I by coming from the bVII… which is a whole tone below. It’s coming “from behind” the tonic, hence the term back door.

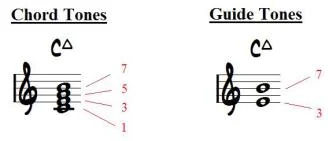

What are “Chord Tones” and “Guide Tones” ?

Chord tones are the notes contained in a chord. For example, a C major 7th chord has the notes C, E, G and B (1-3-5-7) as its chord tones.

Guide tones, on the other hand, are the third and seventh of a chord. For example, a C major 7th chord has the notes E and B (3-7) as its third and seventh. See improvisation lesson using guide-tones.

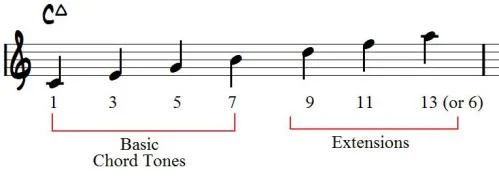

What are chord extensions ?

Simply put the chord tones above the 7th exclusively. Namely the 9th, the 11th and the 13th, even if they are altered. Jazz chords usually contain one or more extensions. For example, basic chord tones and extensions on a Cmaj7 chord:

Exceptions:

7th’s are sometimes considered as an extension in classical theory.

Sometimes, the 6th is part of the chord (example, Cm6) and is NOT perceived as a 13th. Therefore, the 6th (misinterpreted as a 13th) is not always an extension.

Altered Dominant ?

Simply: A dominant 7th chord with one or more “tension notes”. As soon as one alteration exists in a dom 7th chord, we can use the term altered dominant to describe it. It’s common among jazz chords. The alterations are usually created by the presence of an altered 5th and/or 9th by sharpening or flattening. For example : G7(#9, b5) is an altered dominant chord.

Their are many categories of altered dominants… as they come from many different harmonic “regions”: melodic minor modes, harmonic minor modes, other synthetic modes, the symmetrical diminished scale, etc. The available alterations for dominant chords are:

b9

#9

b5

#5

#11

b13

Here’s a series on article on dominant chords, sounds and scales… and here’s a chord chart for altered dominants.

Important note: The chord-scale that is called the altered scale (aka super locrian) is the one that supports a chord with ALL possible alterations. Meaning the b9, #9, b5 and #5.

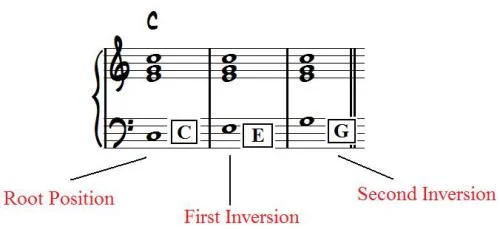

What is an inversion ?

Jazz musicians generally employ the term inversion when talking about the voicing in which a chord is being sounded.

But, in a traditional, or almost classical sense, a chord inversion means to have another chord note played in the bass voice, instead of the root. For example, a C major triad contains the notes C, E and G.

Play with the “C” note in the bottom, we say it’s in root position …

When E, the third, is in the bass it’s called a first inversion …

When G, the fifth, is in the bass, it’s called a second inversion …

For that kind of sound, jazzmen would use the symbols C, C/E and C/G respectively.

So, in jazz then … ?

In a jazz sense, the term inversion can mean the same notes mixed in a different way. For example, we would say that these are the four inversion of the C major 7th (in a drop-2 voicing):

As you can see, the same four notes of C major 7th can be sounded in many different ways. This applies to any or all jazz chords. But it seldom happens that jazz musicians use the nomenclature “second inversion” or “third inversion”. You can say that you know all of your inversions of this-or-that chord, but the role of the lowest note has been delegated to the bass instrument anyways.

You never hear at a jam session: “OK guitar player, play the C major 7th in bar 12 in the second inversion, okay?” … It doesn’t matter since the bass player takes the final decision in playing the lowest note anyways!!!

Final Note : you get the same amount of available inversions as the number of notes contained in any of the jazz chords (because all the notes present in the chord can be played as the lowest note.)

Hence, a three-note chord (triad) can be in root position, first inversion or second inversion…

… or a four-note chord (seventh chord) can be in root position, first, second or third inversion…

… or a five-note chord (a seventh chord with added 9th) can be in root position, first, second, third or fourth inversion…

Allright… I think we’re actually done here!

(-: