Lee Konitz

Feb 01, 2015Legendary Saxophonist Shares his Jazz Improvisation Secrets (10 gradients or 10-step method)

March 2010, listening to Lee Konitz on a Kenny Wheeler album: I researched (and then stumbled upon) something that made me practice jazz guitar in a different way; my lines are now breathing freshness (and I can avoid sounding "dull" most of the time!)

My inspiration is (mostly) this great alto sax player:

Who is he?

According to Wikipedia, Lee Konitz (1927-) is an American jazz composer and alto saxophonist born in Chicago, Illinois. He's generally considered one of the driving forces of Cool Jazz. Konitz was one of the few altoists to retain a distinctive sound in the 40s, when Charlie Parker exercised a tremendous influence on other players. Paul Desmond and, especially, Art Pepper were strongly influenced by Konitz.

Lee Konitz's association with the Cool Jazz movement of the 1940s and 50s, includes participation in Miles Davis' epochal Birth of the Cool sessions, and his work with Lennie Tristano came from the same period.

What Can we Learn From Him?

I recently read an interview with Konitz in Downbeat Magazine from December 1985. You can read this interview HERE..

This interview was mind (and ear) opening for me at first. Then, with a little more research, I stumbled upon hand-written examples from a former student of Lee Konitz (I love the WWW !!!) In the examples, the living legend, Konitz is clarifying his...

10-Step Method (aka 10 Gradients) for Jazz Improvisation

Here's a PDF of the written out examples:

Grab your "10 Steps Method PDF" here!

(transposed for C instruments.)

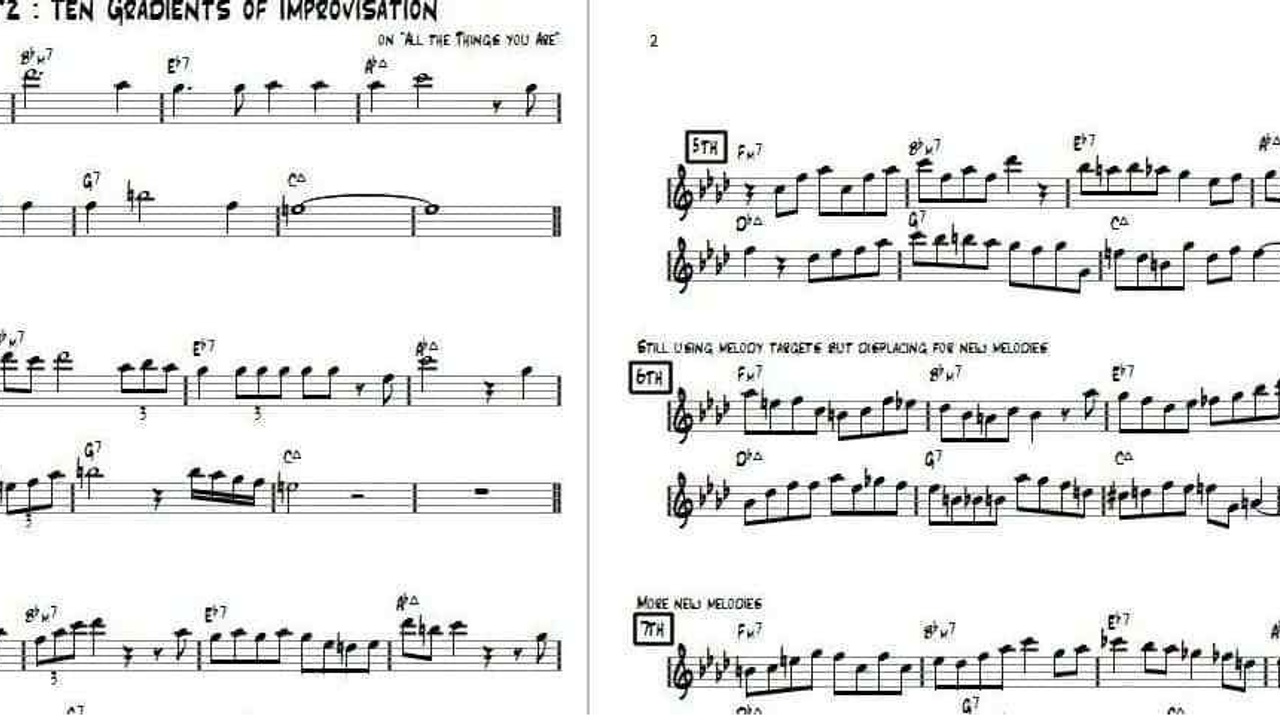

In very brief, the 10 gradients are incrementally moving from simple (the tune's melody) to complicated (improvising from pure inspiration) all the while keeping the original melody as point of departure and reference for building new material. The steps rely less and less on the original melody as we progress, of course.

All examples take place on the first 8 bars of All The Things You Are, a great jazz standard.

What to Do with That ???

Ok, you've read (or played) through the examples and... it doesn't really make any sense, yet? Same thing happened to me, so don't worry! Each of Konitz 10 gradients should be worked on individually for a while. Here's a concise yet detailed explanation of each step:

- 1st Gradient -

The tune's melody, as is. This one's a "no brainer" really. :-)

- 2nd Gradient -

Slight variation on the original: identify "target notes", the most important tones of the melody. Connect them together, when you can or wish, with simple musical devices, with passing tones for example. In this step, the focus is on the important tones. Remember that these can be shortened in duration to allow passing tones to happen.

- 3rd Gradient -

More notes added to the line. Using new devices such as neighbor tones (mostly diatonic), change of direction and skips. The "target notes" are still present on strong beats but there's more flourishes around them. Similar to second gradient, but with more ornaments.

- 4th Gradient -

While it may be hard to tell the difference between Step 2 and 3 ("What should I play now...?"), Step 4 is really straight forward: Imagine a stream of 8th-notes (and occasional triplets) that simply uses the melody notes as guide-tones. That's the "big picture" of step 4. Every improvised lines on guide tones before? Check this out.

- 5th Gradient -

Same as Step 4 (the line is a stream of 8ths and triplets with the melody note dictating the direction) but we're adding two new important devices:

- Neighbor tones (now more chromatic) and arpeggiation of underlying chords.

- Rhythmic displacement of "target notes" (they don't always fall on downbeats anymore.)

That's where the line really starts to develop into "its own thing". Very cool!

- 6th Gradient -

According less importance to the melody again: target notes still appear in their respective bars but may become subsidiary to the other ones (rhythmically, melodically and in phrasing/emphasis). In other words: the ornaments can "take over" and get more attention now. The improvised line should also be built from higher and higher chord tones (extensions such as 9ths, 11ths and 13ths).

- 7th Gradient -

Same as sixth gradient but Lee Konitz is using even more "higher" extension and altered chord tones such as b9, #9 and others. This one is a bit more "out" and chromatic than step 6. It depends on the tune, the player and where the line wants to go.

- 8th Gradient -

Original melody or intervals may still be present but they're totally ingrained in the improvised melody (barely noticeable, or not very obvious). This is probably where most "classic solos" stand: a great improvised line that stems from the original melody but that is never too obviously quoted from the original. Listen to Jim Hall, he's a master at using the melody subtly like this.

- 9th Gradient -

Almost no reference to the original target tones anymore (but the improvised line is still very anchored in the harmony of the tune and has grown from the original melody.) Lee Konitz may well be the only one to fully grasp this "gradient" of improv. I must admit, I don't really get it ... yet! To me, this is mind over matter...

- 10th Gradient -

An act of pure inspiration.

Now, no written example can clearly demonstrate this one. It's very personal and somehow mystical. I suggest you listen to the Kenny Wheeler album Angel Song, the fourth track. Lee Konitz 's solo on this one is a clear demonstration of "pure inspiration".

Melody is King

I hope this Lee Konitz method helps you in your quest in becoming a better improviser. At the very least, it should make you re-consider some melodies you thought you knew.

I really love that whole idea because it all comes before using licks or scales and arpeggios: the tune's melody is enough to go a long way! In the end, it's all about basic ideas and how they're ornamented. In classical music terms: theme and variations.